As I’ve been blogging about the development of a School

Technology Strategy, I’ve also been reading a recently published book called The

Learning Edge by Bain and Weston. It’s a stimulating read in this context because

it positions education as failing technology rather than the traditional reverse. That might not immediately chime with readers but bear with me. A few

days ago I also read an interesting blog

post by Wes Miller in which he explored the concept of ‘Premature

Innovation’ in the context of Microsoft. The combination of these two sources

has got me thinking...

As I’ve been blogging about the development of a School

Technology Strategy, I’ve also been reading a recently published book called The

Learning Edge by Bain and Weston. It’s a stimulating read in this context because

it positions education as failing technology rather than the traditional reverse. That might not immediately chime with readers but bear with me. A few

days ago I also read an interesting blog

post by Wes Miller in which he explored the concept of ‘Premature

Innovation’ in the context of Microsoft. The combination of these two sources

has got me thinking...

Bain & Weston take the reader back to the work of Benjamin Bloom, the

famous Educational Psychologist who in 1984 published ‘The 2 Sigma Problem:

The Search for Methods of Group Instruction as Effective as One-to-One Tutoring’.

In short, Bloom argued that one-to-one tutoring was the most efficient paradigm

for learning but that, at scale, it is not practical or economical. He went on

to say that optimising a relatively small number of significant variables may

in fact allow group instruction to approach the efficiency of one-to-one

tutoring. In this context, of particular interest is whether technology might simulate

one-to-one tutoring effects such as reinforcement, the feedback-corrective loop

and collaborative learning.

The promise of technology in education to date has almost always

exceeded delivery and the blame has usually been attributed to technology. But is it really all the fault of

technology? Well, Bain & Weston make a very interesting point in the

context of Bloom’s research: although Bloom gave us a

very useful framework for educational reform, there has been little systematic

change in classroom practice for decades. The didactic model is still the

beating heart of most schools. The practical implementation of research-based enhancements

to pedagogy and curricula in schools has been painfully slow. In a very real

sense, technology is the gifted student, sitting at the front with a straight

back and bright eyes, full of enthusiasm, and being studiously ignored by educators. Education is failing technology.

Is this the whole

story? Well, I certainly think it’s impossible to divorce a school

technology strategy from an educational strategy with associated pedagogical and

curricular implications. They go hand in hand. For example, a 1:1 ratio of

devices to students is not going to make much of dent in learning in a school if

the underlying pedagogy is predominantly teacher-led (for example). Technology will

only ever leverage the benefits of a sound educational strategy and its practical manifestation. The biggest

challenge for school leaders is therefore to construct a rigorous educational

strategy and drive the change required to manifest it using research and data to drive continuous improvement. I see limited

evidence of this in most schools.

If I’ve convincingly shifted the blame away from technology,

perhaps it’s time to balance the scales a little. When reading Bain &

Weston’s book, I was struck by the fact that a lot of the research focused on

technology that I think fundamentally fails education, regardless of the

education strategy. I think bright eyed, bushy tailed technologists sometimes

suffer from premature innovation. This is where a seemingly great idea

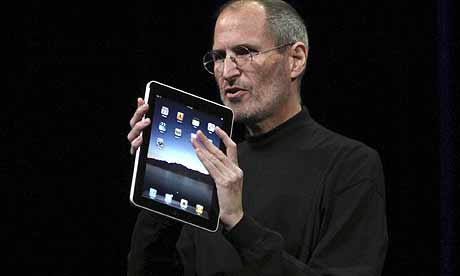

isn’t adopted or fails to fulfil its promise. A startling example from Wes

Miller’s blog is the tablet. Tablets have been around for quite a while with very

limited adoption before Apple stepped into the market. They launched the iPad and

now tablet numbers are burgeoning and 1:1 iPad models for schools seem to fill

every other blog post I read. Why?

As Steve Jobs was well aware, technology does not get used

unless it does what it is designed to do really well and certainly better than

a manual option. In a classroom, technology needs to work at the pace of the learner

and/or the teacher. Even a 5 second delay can interrupt the pace and rhythm of

a lesson. It also needs to be intuitive. It is just not fair to expect every

teacher to be a technology expert and there isn’t time for endless training.

Taking the iPad as an example, it’s hugely popular because a two year old can

use it, it’s personal and mobile, wireless technology and the Internet are have

matured sufficiently to fill it up with engaging content, and it is reliable. It’s turbo-charged book. The time is

right.

Another example of a significant product failure in

education due to premature innovation is the Virtual Learning Environment (or Managed

Learning Environment or Learning Platform or Learning Management System). In the

UK a Government agency called Becta

was responsible for creating a functional specification for this product

category. They then used this specification to put in place a framework off

which schools might procure. The problem was that Becta tried to create an all singing,

all dancing specification and it was just far too detailed. The resulting

software created by the market to meet the requirement was therefore horribly over-engineered.

The outcome? A very significant number of VLE products languishing in schools,

not being used because they’re too difficult. A very big waste of money.

Again, in the VLE space we’re beginning to see disaggregation

of the functional components into bite-size and usable chunks rather than a

monolith with all the agility of a super tanker. Platforms are beginning to

emerge which re-aggregate these simple elements into a manageable whole,

retaining and enhancing usability in the process. The result? I’m beginning to see some interesting products in the

VLE space.

Let’s not ever lose sight of the fact that technology is a

tool and that my School Technology Strategy blog posts are implicitly (and now

hopefully explicitly) intended to sit within the context of an educational

strategy that attacks the 2 Sigma challenge with energy and evidence. Without

educational change, the impact of technology on learning will be a placebo

effect [placebo in the sense that there's nothing fundamentally changing but leaders feel better for ticking the technology box]. It is also the case that, even with a sound educational strategy, technology

will only make a difference if it adheres to some very basic principles of

usability and usefulness, a test that most technology in schools still fails.